If you follow the self-help genre, you’ve likely been bombarded with waves of conflicting advice:

Stay present, but make sure you spend time thinking deeply about what you want out of life, setting goals, and creating checkpoints to measure progress.

Find a flow state in your work, but expand your perspective of time so you’re assigning things their proper weight.

Drive results today, but sharpen your strategic mind by thinking multiple steps ahead and considering higher-order consequences to outmaneuver your opponents.

All of this advice on what timeframe to orient towards becomes exhausting. Am I over-indexing on the future and paying too little attention to today? Am I making shallow decisions and not thinking far enough ahead? Am I setting goals that match the optimal timeframes?

Each piece of advice on its own seems intoxicating. But when you try to reconcile these ideas against each other, it’s easy to get stuck. No one tells you how to achieve balance or what that looks like.

The reality is there aren’t just two timeframes in life—present-oriented or future-oriented. These are just the bookends, there are other timeframes that sit in between. But the bookends are the most powerful timeframes to operate in. And the middle proves to be the most dangerous.

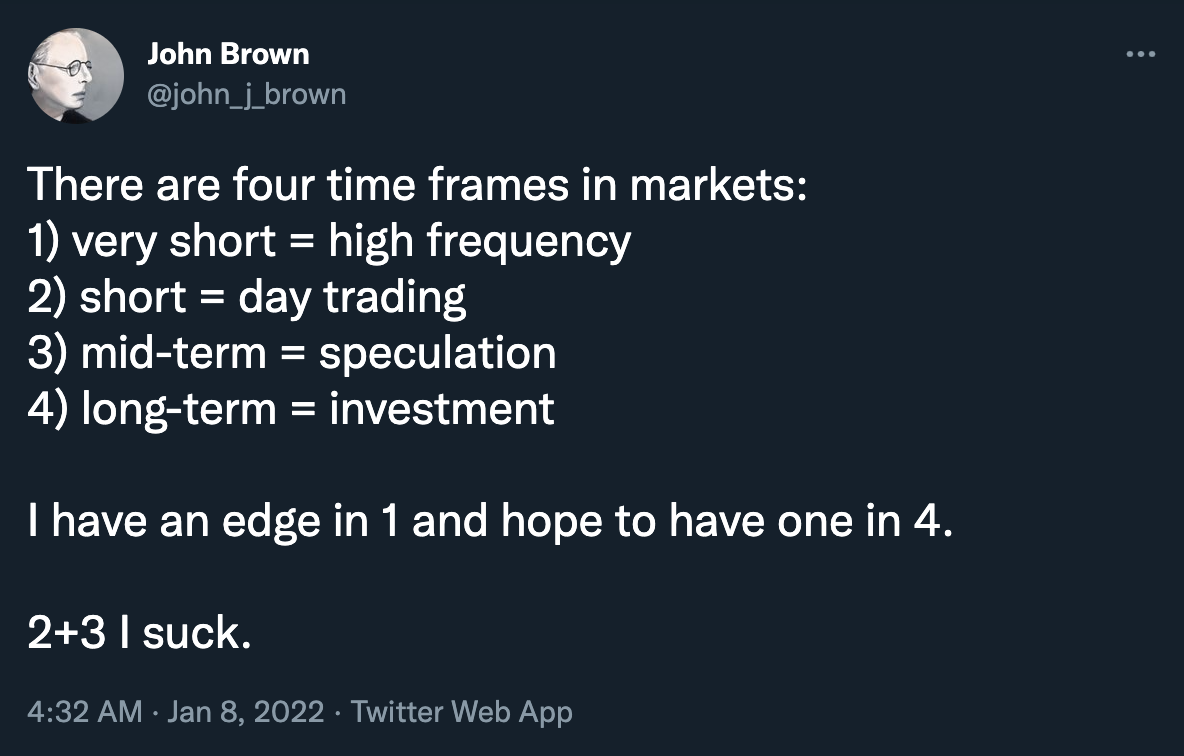

A few weeks back, I came across a post on Twitter from @john_j_brown that provided me with a framework that created clarity…

While this post is geared towards investors, a similar model can be applied to the timeframes in our lives.

There are four timeframes in life…

1) Immediate = today

2) Short = days/weeks

3) Mid-term = months

4) Long-term = years/decades

The most rewarding life is found by pursuing a balance of 1 and 4 and avoiding too much time in 2 and 3. The most dangerous timeframes in life are the short and mid-term.

What’s the barbell strategy?

The optimal balance for these timeframes can be framed similarly to Nassim Taleb’s barbell investment strategy which proposes that you be as hyperconservative and hyperagressive as you can be, instead of being mildly aggressive or conservative.

In life, the parallels are the immediate and long-term. Using the barbell strategy, we should spend 40% of our time focused on the immediate term, 40% on the long term, and only 20% of our time in the middle thinking about short or mid-term. Of course, this is just a mental model. No one is going to sit around and calculate how much time they spend in each category. But as a rule of thumb, it’s an effective way to keep yourself in check and balance the most effective timeframes to operate in.

Why optimize for the immediate and long-term?

1 and 4 are where I find fulfillment in the work itself and a connection to a more meaningful vision I’m working towards. 2 and 3 are where I become impatient, anxious, and scattered—anticipating that presentation next week which distracts me from putting in the work today, fueling unrealistic expectations before reaching sustainable growth, or making shallow decisions that optimize for comfort.

The immediate-term (1) allows you to be fully present and immersed in your work. It helps you remain focused instead of anticipating any sort of future payoff or conflict. This is what allows you to achieve a relaxed state of concentration. The gratification is in the work itself.

While longer timeframes (4) allow for calmness, perspective, and compounding. Thinking in terms of years or decades connects you back to the bigger picture. It also combats the tendency to exaggerate the magnitude of conflicts we face on a shorter time horizon and guards you against deceiving yourself into short-sighted moves that favor comfort and predictability. The long term is what smooths out the anxiety and steadies the waves that can break your knees.

It’s when you become consumed by the short and mid-term (2 and 3)—the days, weeks, and months ahead—that patience and focus give way to restlessness and anxiety. In this timeframe, you’re anchored to unrealistic expectations of linear, short-term growth which compromises strategic thinking and your connection to your ultimate goal.

When you’re focused on the moment in front of you, you’re not anticipating. You’re absorbed in your work. When you’re focused on the longer term, you connect to something larger than yourself and expand your perspective of time. Ego is what operates in the mid-term. It breaks your flow state by anticipating rewards, results, and external validation. It’s what scares you into seeking predictability and comfort to protect yourself—limiting your available upside.

The allure of the short and mid-term is so strong because it’s easy. People who are better at talking than doing thrive in these timeframes. It allows them to create the illusion of progress through seemingly intelligent observations without putting in the work or holding themselves accountable to the long-term results. These are the politicians, the academics, the suits, and the startup flakes who prove unable to stick it out.

Many people live their entire lives here. They’re simultaneously distracted and not thinking long-term enough. They’re living for the weekend, their next vacation, or the comfort of their annual bonus. It’s the most comfortable place to operate, but the least rewarding because the short and mid-term are the most shallow timeframes.

Real depth is found in the immediate and distant—putting in the work today and building up the endurance to sustain for years.

Certainly, you need some balance of the short (2) and mid-term (3) as checkpoints and it’s important to have things to look forward to. And of course, there are obvious exceptions. But sustainable results don’t appear over the course of weeks or months. They appear through years and decades of hard work and a constant connection to what you find meaning in.

Growth is nonlinear

Remember, growth is nonlinear. People tend to overestimate what they can accomplish in the short term and underestimate what they can accomplish over the course of years. The power of small, calculated decisions grows exponentially over time. Especially if you have a clear vision that you’re working towards. Start small and let compound interest run its course.

Focus on the short and mid-term is what interrupts this. Because growth is not always observable in comparison to the previous week or month. When you expect linear results equivalent to the effort you’re putting in, you’re bound to give up too early or make short-sighted decisions that create the illusion of progress at the expense of sustainable long-term growth.

If you’re playing the long game, 1 and 4 are where you build up the resilience and endurance required to contribute your best work. This is what allows you to continue showing up or making difficult decisions that sacrifice comfort for growth.

Optimizing for this balance of immediate and long-term timeframes allows you to persevere. To find meaning in the moment and the work in front of your face, while continuing to come back to your underlying strategy. One that extends beyond the weeks and months, but that you can advance in the moment. Dedicating more of your energy to 1 and 4 allows you to bring your best work to life by ignoring the distractions and noise that sit in between.

What’s in it for you?

When you adopt the barbell strategy for investing your time, you’re able to accelerate your trajectory and outpace those operating in the mid-term. Those who spend 80% of their time focused on the short and mid-term often end up stuck in dead-end careers. They’re prisoners seeking comfort and predictability in the weeks and months ahead. Their trajectory and growth are limited as a result.

The barbell approach encourages a deeper connection to your work and an understanding of what kind of life you want to live. If you know what you want out of life and you’re willing to put in the work, the competition crumbles. It becomes a race against yourself.

But you must never trick yourself into believing you are above the work. The work is where you find solace. Pairing this with the long term and what you’ve defined to be a meaningful life is what allows you to create enduring work and transform yourself. In both the moments you have today and in the decades ahead.

“As one achieves focus, the mind quiets. As the mind is kept in the present, it becomes calm. Focus means keeping the mind now and here. Relaxed concentration is the supreme art because no art can be achieved without it.”

Immediate, distant, but avoid the in-between

When you’re focused on the moment in front of you, that’s where you begin to hone your craft and unlock a flow state so you’re able to do your best work.

When you’re immersed in a longer time horizon, that’s when you’re connected to something bigger than yourself and tap into your strategic mind, allowing you to drive towards your vision.

But when you’re stuck in the middle, that’s where anxiety, anticipation, and ego take hold. Because it’s too soon for most results, distracts you from putting in the actual work, and leads you to cling to the comfort of the familiar in order to avoid the discomfort of introspection—who you are, what you want, the challenges you’ll face, and the work you need to do today to get there.

The sweet spot is found by immersing yourself in your work, achieving a state of flow, and appreciating the moment. But also remaining connected to a greater sense of meaning you find in your life and harnessing the power of your strategic mind.

The best endurance athletes in the world demonstrate this. Consider your strategy, focus on the mile in front of you, and dig deep to stay connected to the reason that keeps you going. The mid-term serves as a hydration station on your path, a place to refuel. But it’s nothing more than that—a brief checkpoint. Then it’s back to putting in the miles and honing your strategy. Leave nothing on the table.